Check Out: A Billy Savage Short Film on John Finley Scott! (Make sure to watch both the Finley 1 and Finley 2 clips)

By John Schubert

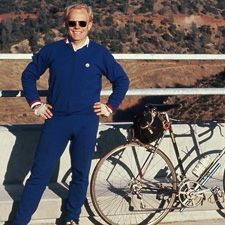

John Finley Scott, pioneer of mountain bikes and cycling advocacyWhat legacy do we leave behind? For John Finley Scott, it’s a complex question, tragically cut short at 72. Known for his irreverent wit and no-nonsense attitude, Scott, a retired University of California at Davis sociology professor, unexpectedly vanished on June 3, 2006. For anyone familiar with his intensely social nature, his disappearance signaled something was deeply wrong. His bikes remained untouched, his car unmoved, and his home undisturbed. Yet, he was simply gone, leaving behind a void in the cycling community and a chilling mystery.

John Finley Scott, pioneer of mountain bikes and cycling advocacyWhat legacy do we leave behind? For John Finley Scott, it’s a complex question, tragically cut short at 72. Known for his irreverent wit and no-nonsense attitude, Scott, a retired University of California at Davis sociology professor, unexpectedly vanished on June 3, 2006. For anyone familiar with his intensely social nature, his disappearance signaled something was deeply wrong. His bikes remained untouched, his car unmoved, and his home undisturbed. Yet, he was simply gone, leaving behind a void in the cycling community and a chilling mystery.

Suspicious financial activity linked to Scott’s bank account both before and after his disappearance, coupled with blood found in his home, painted a grim picture. Police identified a “person of interest,” offering little solace to those who knew and loved him. Having never personally known someone close to a suspected murder, the reality of the situation was unsettling. The identified individual, Charles Kevin Cunningham, had a history with Scott, having been hired for home maintenance and later caught cashing a stolen check reported by Scott. Cunningham’s subsequent incarceration on other charges offered a small measure of legal progress, but the larger question of Scott’s fate remained. Captain Larry Cecchettini of the Yolo County Sheriff’s Department affirmed the ongoing investigation, acknowledging the slow pace of real-world crime labs compared to television dramas.

So, who was John Finley Scott, and why highlight his story now, especially considering the tragic circumstances? Scott was, simply put, a monumental figure in cycling history, a pioneer whose contributions deserve recognition. His influence on the bikes we ride today and the laws that govern cycling is profound, making his absence all the more keenly felt.

John Finley Scott's "Woodsie Bike," an early precursor to modern mountain bikesLet’s rewind to 1953. In this year, John Finley Scott achieved something remarkable: he built what is recognized as the world’s first mountain bike. He christened it his “woodsie,” a testament to its intended terrain. This wasn’t just any bike; it featured multiple gears and knobby tires – innovations decades ahead of their widespread adoption. Fast forward to the early 1970s, and Scott’s impact shifted to legislative realms. He played a pivotal role in persuading the California legislature to adopt sensible traffic laws for bicycles. Crucially, he advocated for classifying the bicycle as a vehicle, preventing its relegation to sidewalks and restrictive stop requirements at every driveway. The significance of this achievement cannot be overstated. California’s traffic laws often set a precedent for other states and the National Uniform Vehicle Code. Without Scott’s intervention, cyclists nationwide could have faced severely limited riding conditions, confined to sidewalks and slowed to pedestrian speeds.

John Finley Scott's "Woodsie Bike," an early precursor to modern mountain bikesLet’s rewind to 1953. In this year, John Finley Scott achieved something remarkable: he built what is recognized as the world’s first mountain bike. He christened it his “woodsie,” a testament to its intended terrain. This wasn’t just any bike; it featured multiple gears and knobby tires – innovations decades ahead of their widespread adoption. Fast forward to the early 1970s, and Scott’s impact shifted to legislative realms. He played a pivotal role in persuading the California legislature to adopt sensible traffic laws for bicycles. Crucially, he advocated for classifying the bicycle as a vehicle, preventing its relegation to sidewalks and restrictive stop requirements at every driveway. The significance of this achievement cannot be overstated. California’s traffic laws often set a precedent for other states and the National Uniform Vehicle Code. Without Scott’s intervention, cyclists nationwide could have faced severely limited riding conditions, confined to sidewalks and slowed to pedestrian speeds.

Scott collaborated with activist John Forester in this legislative battle. Forester himself acknowledged Scott’s superior skill in navigating bureaucratic processes, admitting, “He was much more adept at handling bureaucracies than I was.” Forester even valued Scott’s editorial input, noting Scott’s ability to refine Forester’s writing for American audiences. While Forester was known for his directness, Scott wielded a disarming professorial charm, a tool he used effectively to advance cycling’s cause. This strategic approach proved successful. California’s resulting legislation, while not flawless, successfully averted a nationwide trend that could have marginalized cyclists significantly. Scott later revealed that certain complexities and wordiness in the law were deliberately introduced to ensure broader support and the most favorable outcome for cyclists. This nuanced understanding of human behavior and legislative maneuvering was a hallmark of Scott’s approach.

Scott’s next major contribution to cycling emerged in the mid-1970s. He provided crucial early business capital to a young bike racer named Gary Fisher, investing $10,000. This investment was instrumental in launching the mountain bike as a viable product. The funds enabled Fisher to purchase mountain bike frames, handcrafted by Tom Ritchey, and components from around the world. Fisher then assembled and sold complete mountain bikes, priced around $2,000 each. Again, Scott’s influence here is hard to overstate. The widespread availability of mountain bikes we enjoy today might never have materialized without his early financial backing and vision.

Why is this claim so significant, especially given that the mountain bike already existed in concept? Because Scott’s investment helped prove its market viability. In 1977, the prevailing view was that mountain biking was a niche activity, a “weird California thingie,” not a commercially viable product. When Joe Breeze sold a limited run of 10 Breezer mountain bikes, many believed the market was saturated. Scott’s venture capital allowed Fisher to sell hundreds of bikes, demonstrating sufficient demand to attract the attention of major manufacturers like Specialized and Univega. By late 1982, these companies began offering production mountain bikes. It’s doubtful they would have taken this leap based solely on Breeze’s initial small run.

John Finley Scott with students, advocating for vehicular cycling principlesAt the University of California, Davis, Scott was known as a thought-provoking professor who challenged his students’ assumptions. His sociology of transportation class offered insights that remain relevant, even amidst evolving bicycle advocacy approaches. Susan Borschel, a former student and admirer of Scott, now a lawyer in Washington, DC, recalls his core principle: “He always promoted the notion that bicycles should be treated like cars.” She elaborates, “We shouldn’t have special treatment just because we’re on bicycles. If we acted like vehicles and were treated that way, we’d be safer. I thought that was very different and cutting edge.” This vehicular cycling concept was indeed novel at a time when many advocated for separate, often marginalized, treatment for cyclists.

John Finley Scott with students, advocating for vehicular cycling principlesAt the University of California, Davis, Scott was known as a thought-provoking professor who challenged his students’ assumptions. His sociology of transportation class offered insights that remain relevant, even amidst evolving bicycle advocacy approaches. Susan Borschel, a former student and admirer of Scott, now a lawyer in Washington, DC, recalls his core principle: “He always promoted the notion that bicycles should be treated like cars.” She elaborates, “We shouldn’t have special treatment just because we’re on bicycles. If we acted like vehicles and were treated that way, we’d be safer. I thought that was very different and cutting edge.” This vehicular cycling concept was indeed novel at a time when many advocated for separate, often marginalized, treatment for cyclists.

Scott recognized and often highlighted the “hegemony of the automobile,” acknowledging its entrenched role in society. He observed that even in cycling-friendly nations like the Netherlands, bicycle usage was declining while car use increased. He noted a similar trend in Davis, where contemporary college students favored buses over bicycles compared to previous generations. Scott argued that bicycle commuting was unlikely to achieve significant growth in upwardly mobile societies, especially in the U.S., emphasizing cars as “efficient status symbols” unlikely to be readily abandoned.

However, Scott also acknowledged the enduring popularity of weekend recreational cycling. His personality was a blend of delight and provocation. Whether awarding a prize at the Davis Double Century for the first finisher without Campagnolo components or humorously telling his sorority students about their marital prospects, he wasn’t afraid to challenge norms. He critiqued those who disparaged American culture and surprisingly defended Walmart. In online cycling forums, he saw it as his role to challenge what he perceived as anti-car sentiments, believing this agenda harmed vehicular cycling principles. This often led to clashes with well-intentioned individuals, causing unnecessary friction.

Then, there was the iconic double-decker bus. Scott owned a London double-decker bus, famously used to transport groups of cyclist racers, often with memorable outcomes. Joe Breeze, a five-time tandem winner of the Davis Double Century and founder of Breezer bicycles, recounted a story from decades ago when the bus departed without Scott. “We were at a rest stop, we got in, someone else was driving, and we took off,” Breeze recalled. “No one realized Scott wasn’t in the bus. And then a police car came up to us with its lights flashing, and pulled us over. Scott was in the police car.”

The thought of Scott arriving in a police car today is poignant. John S. Allen, author of Street Smarts and a nationally recognized bicycling policy analyst, reflected, “Scott was too dismissive of the potential of bicycling for transportation, but he was very spot on about some of the false assumptions people make. I miss the guy. He’s someone I could discuss things with, and no one else is as much fun. And the way he went was just terrible. Unexpected, violent, undeserved, a weird fluke of just apparently allowing the wrong person in his life.”

This article about John Finley Scott, penned by John Schubert, originally appeared in the January 2007 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine, the publication of the Adventure Cycling Association. For further details, visit: www.adventurecycling.org.

Copyright 2007 by John Schubert

CONVICTED FELON FOUND GUILTY OF MURDER (Excerpts from an article by Jason Norman in the December 2007 issue of BRAIN, a bicycle retailer publication)

Yolo County jurors delivered a guilty verdict against Charles Kevin Cunningham, a tree trimmer and convicted felon, for the 2006 murder of John Finley Scott, the man widely credited with inventing the mountain bike.

Cunningham, 48, was convicted of first-degree murder and grand theft, facing a sentence of 32 years to life.

Despite the absence of Scott’s body, the circumstances of his disappearance and a bloody crime scene at his residence convinced the jury of his murder.

While forensic evidence directly linking Cunningham to Scott’s murder was limited, the deputy district attorney successfully argued motive. Scott, 72, had discovered Cunningham forging his signature on checks and confronted him. Cunningham had been employed by Scott for tree trimming services.