The somber ritual of the ghost bike installation has become a recurring scene in cities around the world. Recently, in Toronto, another white-painted bicycle appeared, this one marking the spot where Ali Sezgin Armagan tragically lost his life after being struck by a construction vehicle. Organized by Joey Schwartz of Advocacy for Respect for Cyclists (ARC), a group ride converged at the site, transforming grief into a visible symbol of loss and a potent demand for change.

Joey Schwartz of Advocacy for Respect for Cyclists (ARC) at a ghost bike installation ceremony for a cyclist killed in Toronto.

Joey Schwartz of Advocacy for Respect for Cyclists (ARC) at a ghost bike installation ceremony for a cyclist killed in Toronto.

Avenue Road, a major artery in Toronto, became the site of this latest memorial, with a large crowd gathering to participate in the ghost bike ride. The procession, stretching across three southbound lanes, was a stark reminder of the vulnerability cyclists face daily on urban roads designed primarily for cars. Among the participants were families, their presence underscoring the community-wide impact of such tragedies and the shared hope, as expressed by one attendee named Emma, that this would be the last memorial ride they would need to attend.

The Haunting Reality of Ghost Bikes

Ghost Bikes are more than just painted bicycles; they are powerful symbols. These stark white memorials serve as roadside markers commemorating cyclists who have been killed or severely injured by vehicles. Typically installed near the site of the incident, ghost bikes act as poignant reminders of the human cost of traffic collisions and advocate for safer cycling conditions.

These memorials are not new. The first ghost bike is believed to have appeared in St. Louis, Missouri, in 2003. Since then, the practice has spread globally, with ghost bikes appearing in cities across North America, Europe, South America, and Australia. Each ghost bike represents a life lost, a story cut short, and a community’s collective grief and demand for change.

Families and even dogs join a ghost bike memorial ride in Toronto, highlighting community support for cycling safety advocacy.

Families and even dogs join a ghost bike memorial ride in Toronto, highlighting community support for cycling safety advocacy.

The Toronto incident involving Ali Sezgin Armagan is not an isolated event. Tragically, this stretch of Avenue Road has witnessed multiple cyclist fatalities in recent years, many involving large construction vehicles. This grim pattern highlights a systemic issue: the dangers posed by urban development and construction traffic to vulnerable road users.

A History of Loss and a Persistent Call for Change

The issue of cyclist deaths in Toronto, particularly involving construction vehicles, is not a recent phenomenon. The author recalls participating in their first ghost bike ride in 2006 for Hubert Van Tol, a University of Toronto professor killed by a dump truck. Van Tol’s death, like Armagan’s, was linked to the construction industry, highlighting a long-standing and tragically persistent problem.

A ghost bike serves as a somber reminder of cyclist deaths, a tradition that started as early as 2006 with memorials like this one for Hubert Van Tol.

A ghost bike serves as a somber reminder of cyclist deaths, a tradition that started as early as 2006 with memorials like this one for Hubert Van Tol.

Even after Van Tol’s death, cycling advocates were already calling for regulations requiring side guards on trucks – a safety measure that remains insufficiently implemented to this day. This lack of progress underscores the slow pace of change and the continued vulnerability of cyclists in urban environments.

In the case of Ali Sezgin Armagan, initial reactions on social media wrongly blamed the victim. However, police reports indicated that the truck driver was charged with careless driving causing bodily harm or death. Armagan, a recent immigrant from Turkey working as an Uber delivery cyclist, represents a particularly vulnerable demographic often navigating busy city streets to make a living.

Participants observe a moment of silence during a ghost bike installation for Ali Sezgin Armagan, killed while cycling in Toronto.

Participants observe a moment of silence during a ghost bike installation for Ali Sezgin Armagan, killed while cycling in Toronto.

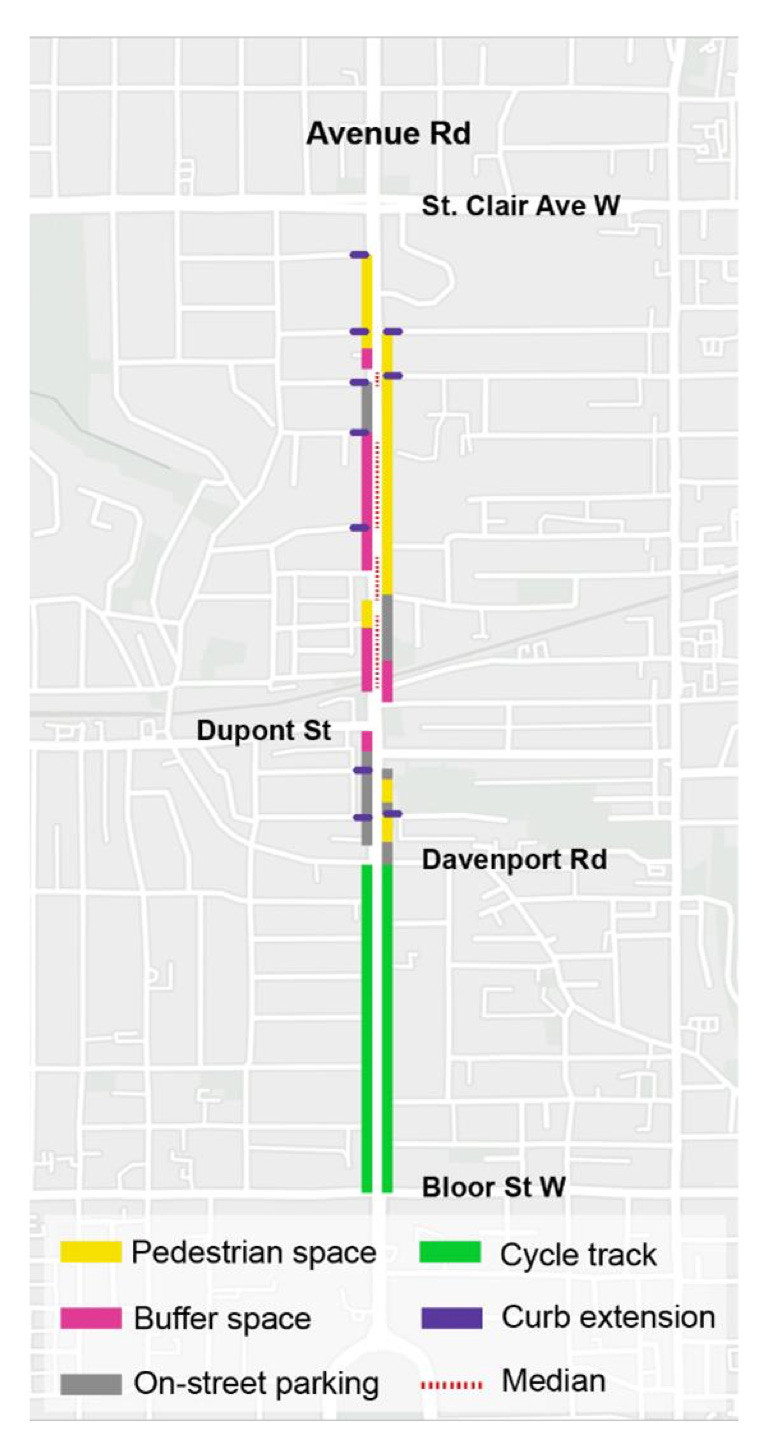

Prioritizing Traffic Flow Over Cyclist Safety

Despite years of study and advocacy, improvements to Avenue Road and similar thoroughfares remain stalled. A recent report revealed that a significant portion of the public prioritizes maintaining fast-moving traffic flow for cars, even at the expense of cyclist and pedestrian safety. Concerns about congestion and traffic flow outweigh considerations for vulnerable road users, perpetuating a dangerous environment for cycling.

A city report reveals public resistance to road safety improvements for cyclists, prioritizing car traffic flow over vulnerable road user safety.

A city report reveals public resistance to road safety improvements for cyclists, prioritizing car traffic flow over vulnerable road user safety.

This resistance to change is further highlighted by the quote, “You can’t justify a bridge by the number of people swimming across a river.” The low numbers of cyclists and pedestrians on roads like Avenue Road are not due to lack of desire, but rather a direct consequence of the perceived and very real danger these roads pose. People are not cycling or walking because it feels unsafe, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy where lack of use is then used to justify inaction on safety improvements.

Construction Industry’s Responsibility

The author argues that cyclist deaths, especially those involving construction vehicles, are not simply accidents but the result of systemic failures. These failures stem from:

- Oversized and poorly designed vehicles: Construction vehicles are often large, have significant blind spots, and lack crucial safety features like side guards.

- Inadequate driver training: Drivers of these heavy vehicles may not receive sufficient training on safely navigating urban environments and sharing roads with cyclists and pedestrians.

- Industry prioritization of speed and profit: Tight schedules and economic pressures within the construction industry can incentivize risky driving behaviors and a disregard for safety.

This issue is not new. In 2021, the death of 18-year-old Miguel Joshua Escanan, also killed by a ready-mix truck on Avenue Road, prompted similar calls for industry reform. The construction boom in many cities exacerbates this problem, increasing the number of heavy vehicles on roads and intensifying the risks for cyclists.

The installation of a ghost bike as a stark memorial at the site where a cyclist tragically lost their life, urging for safer streets.

The installation of a ghost bike as a stark memorial at the site where a cyclist tragically lost their life, urging for safer streets.

A close-up view of a newly installed ghost bike, painted white and locked to a pole, standing as a silent vigil for a fallen cyclist.

A close-up view of a newly installed ghost bike, painted white and locked to a pole, standing as a silent vigil for a fallen cyclist.

Safety as a Choice: Learning from Copenhagen and Europe

The real estate industry’s perspective, as quoted in the original article, bluntly reveals a dangerous prioritization of economic gain over human safety: “Has this person ever given any thought to the sizable contribution to the gross domestic product one condo building makes; has anyone?” This statement encapsulates a societal attitude where cyclist safety is seen as secondary to economic development.

However, examples from cities like Copenhagen demonstrate that prioritizing safety and economic progress are not mutually exclusive. Copenhagen routinely implements safe bike lane diversions and protective measures at construction sites, proving that safety can be integrated into urban development. The difference lies in a conscious choice and a societal value system that prioritizes the well-being of all road users.

Construction dump trucks obstructing a bike lane in Toronto, illustrating the dangers cyclists face due to construction vehicle traffic and inadequate infrastructure protection.

Construction dump trucks obstructing a bike lane in Toronto, illustrating the dangers cyclists face due to construction vehicle traffic and inadequate infrastructure protection.

Example of safe bike lane diversion during construction in Copenhagen, contrasting with less safe practices in North America.

Example of safe bike lane diversion during construction in Copenhagen, contrasting with less safe practices in North America.

The Need for Systemic Changes: Trucks, Training, and Infrastructure

Improving truck design is crucial. European cities are increasingly adopting trucks with enhanced visibility, minimizing blind spots that are particularly dangerous for cyclists and pedestrians. Side guards, another relatively simple safety measure, are still not mandated in many North American cities, despite evidence of their effectiveness in preventing serious injuries and fatalities.

Studies, like one prepared for the City of Toronto in 2019, have consistently highlighted the poor visibility from large trucks as a major contributing factor in collisions with vulnerable road users. Mandating side guards and promoting the adoption of safer truck designs are essential steps.

Research highlighting the poor visibility from large trucks, a significant factor in collisions involving cyclists and pedestrians.

Research highlighting the poor visibility from large trucks, a significant factor in collisions involving cyclists and pedestrians.

Side guards and safety signage on trucks in London, demonstrating a safety feature that could prevent cyclist fatalities.

Side guards and safety signage on trucks in London, demonstrating a safety feature that could prevent cyclist fatalities.

Beyond vehicle design, better driver training and stricter oversight of trucking companies are necessary. The case of John Offutt, killed by a ready-mix truck driver with a history of traffic offenses, underscores the need for improved driver screening and ongoing monitoring.

Furthermore, urban planning and zoning policies play a significant role. Toronto’s zoning regulations, which restrict development to main streets and former industrial areas, contribute to increased construction and truck traffic. The lack of smaller apartment buildings in residential zones forces development to be concentrated in large, concrete-intensive projects, further increasing the demand for construction vehicles.

The intersection on Avenue Road in Toronto where a cyclist was fatally struck, highlighting a dangerous urban road design.

The intersection on Avenue Road in Toronto where a cyclist was fatally struck, highlighting a dangerous urban road design.

Zoning regulations in Toronto restrict the development of smaller, low-rise apartment buildings, contributing to increased construction and truck traffic.

Zoning regulations in Toronto restrict the development of smaller, low-rise apartment buildings, contributing to increased construction and truck traffic.

A Future Where Cyclists are Safe

Creating safer streets for cyclists is not just about preventing tragedies; it’s also about promoting sustainable transportation and reducing carbon emissions. Encouraging cycling as a viable mode of transport is crucial for environmental sustainability and urban livability. However, this requires a fundamental shift in priorities, where cyclist safety is not compromised for the sake of speed, profit, or outdated urban planning models.

Ghost bikes stand as silent but powerful calls for this change. They are memorials to lives lost, but also potent symbols of hope for a future where cities prioritize the safety and well-being of all road users, not just those in cars. The memory of Ali Sezgin Armagan, Hubert Van Tol, Miguel Joshua Escanan, and countless others demands action. The construction industry, city planners, and policymakers must embrace their responsibility to create urban environments where cycling is safe, respected, and encouraged. Dead cyclists cannot be seen as simply a cost of doing business; their lives matter, and their memorials must inspire lasting change.