Unless you’re part of the motorcycle community, you might not be familiar with Biker Cuts – vests born from denim and leather jackets. These aren’t just pieces of clothing; they are powerful symbols within biker culture, often adorned with “colors” or patches that tell a story of belonging, rebellion, and identity.

The biker cut is more than just apparel. It’s a historical artifact reflecting the evolution of American motorcycle culture, a defiant gesture against mainstream society, and a deeply meaningful garment for those who wear it. Let’s delve into the fascinating history of this iconic piece of outlaw style.

The Genesis of the Biker Cut

Capital City Motorcycle Club, 1938. Image via Valcom News

Capital City Motorcycle Club, 1938. Image via Valcom News

The narrative of biker cuts begins with the rise of motorcycle clubs in the early 20th century. In 1924, the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) was established. Initially, the AMA aimed to support the burgeoning motorcycle industry and foster a community of riders. Early motorcycle clubs, emerging in the 1920s and 1930s, adopted a uniform style that reflected practicality and camaraderie. Think heavy sweaters, varsity jackets, and overalls – attire that, while functional, lacked the rebellious edge associated with biker style today.

The AMA played a role in shaping this early aesthetic by hosting events and awarding prizes for the best-dressed clubs. This spurred the use of club patches as identifiers. These early motorcycle uniforms were about practicality and club unity rather than projecting a tough “biker” image. Riding pants and cozy sweaters projected an image of sportsmen, not rebels. However, the world was on the brink of change, and World War II would significantly alter both motorcycle culture and biker fashion.

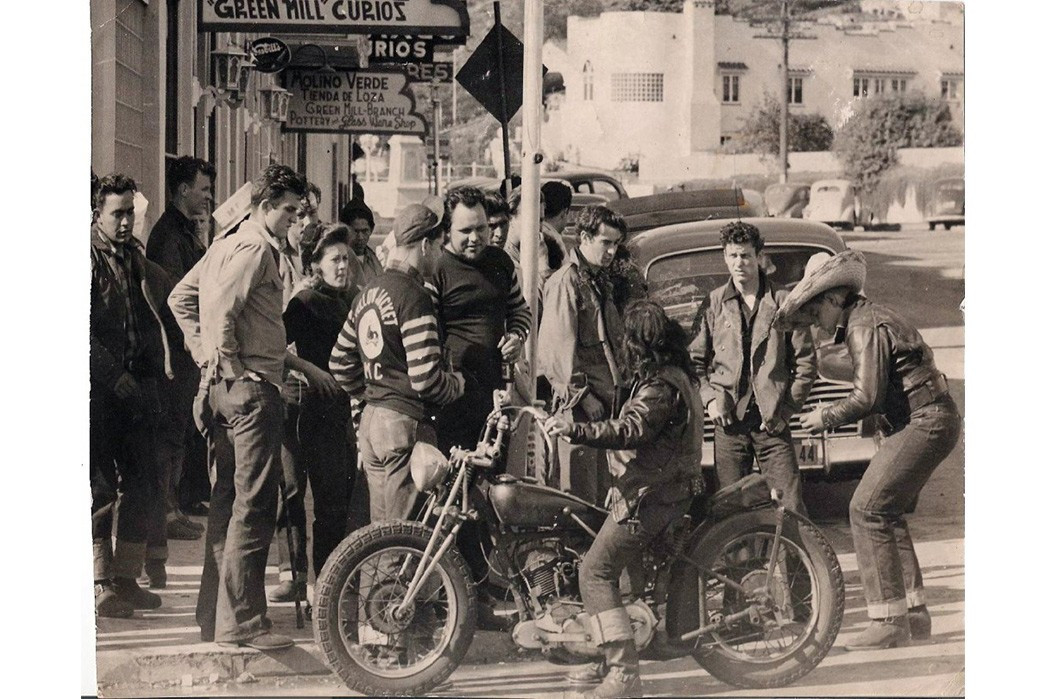

Hollister 1947. Image via Cahiers de Mode.

Hollister 1947. Image via Cahiers de Mode.

The return of veterans after World War II brought about a stylistic shift. Military-issued leather flight jackets, khakis, and blue jeans became popular civilian attire. These garments, worn with a casual flair, were perfectly suited to the demands of motorcycle riding. While leather jackets, like the iconic Perfecto jacket by Irving Schott, existed before the war, they were often styled more formally.

It was the worn, personalized leather flight jackets brought home by veterans – often adorned with artwork and patches – that redefined motorcycle style. These jackets shifted the perception of leather from formal wear to rugged individualism. Post-war, leather jackets moved away from catalog formality, embracing a more rebellious style popularized by figures like Marlon Brando.

World War II had a profound societal impact. Millions of American men experienced unprecedented camaraderie and trauma during the war. Upon returning home, they faced pressure to conform to a new post-war ideal of domesticity and corporate life. Men were encouraged to settle down, marry, and embrace conventional careers, often in the newly burgeoning corporate landscape, symbolized by the “gray flannel suit.”

However, many veterans sought camaraderie and a sense of belonging outside of societal expectations. Motorcycle clubs became a haven for these men, offering social connection, a shared sense of adventure, and a way to cope with the psychological aftermath of war, including PTSD. These groups, however, soon attracted unwanted attention from authorities.

The late 1940s saw the publication of the Kinsey report, a groundbreaking study on human sexuality. Despite its flaws, the report sparked public discussion about sexuality, challenging societal norms. This, coupled with post-war anxieties, led authorities to view male bonding and groups like motorcycle clubs with increased suspicion, reflecting America’s complex and often unspoken relationship with male intimacy and sexuality.

Hollister. Image via Practical Machinist.

Hollister. Image via Practical Machinist.

The 1947 Hollister Riot became a watershed moment, forever altering the trajectory of American motorcycle clubs. Hollister, California, had hosted the AMA’s Gypsy Tour since the 1930s but cancelled it during the war years. The 1947 event marked its return, drawing an unexpectedly massive crowd of 4,000 motorcyclists to the small town. Fueled by alcohol, the gathering overwhelmed the local police force. While actual crime and injuries were minimal, a sensationalized Life magazine article exaggerated the events, portraying the bikers as out-of-control criminals. In 1953, the film “The Wild One,” starring Marlon Brando, further dramatized the Hollister events, cementing the image of bikers as rebellious outlaws in the public consciousness.

This overblown media portrayal had a radicalizing effect on biker culture. In response to the negative publicity, the AMA issued a statement claiming that 99% of motorcyclists were law-abiding citizens, and only 1% were outlaws. This statement, intended to distance the AMA from the “bad” bikers, inadvertently gave rise to the “1% outlaw” motorcycle clubs.

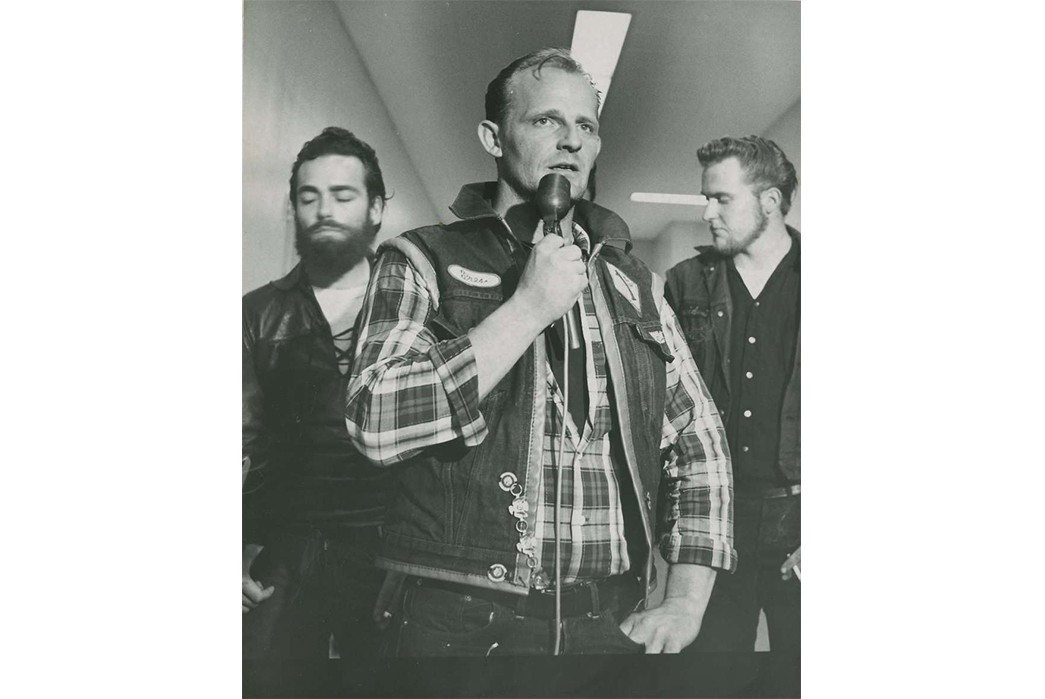

The Rise of the 1% Outlaws and the Biker Cut

Hell’s Angels member in his colors. Image via San Francisco Chronicle.

Hell’s Angels member in his colors. Image via San Francisco Chronicle.

The fallout from the Hollister incident, and the AMA’s reaction, led to a significant split within motorcycle culture. The “1%” statement became a badge of honor for those who embraced the outlaw image. These “One-Percenters” deliberately positioned themselves outside of mainstream motorcycle culture and the AMA’s control, leading to the formation of outlaw motorcycle groups (OMGs). The diamond-shaped “1%” patch, seen on the vest in the image above, became an instantly recognizable symbol of this outlaw identity.

The motorcycle club landscape fractured into two distinct categories: the 99-Percenters, clubs sanctioned by the AMA, and the One-Percenters, the outlaw clubs. This division extended to their visual identities, particularly the way they wore their “colors” – the patches signifying club membership.

Model wearing Iron Heart 21oz Selvedge Denim Modified Type III Vest (front and back view)

Model wearing Iron Heart 21oz Selvedge Denim Modified Type III Vest (front and back view)

It was in this environment of burgeoning outlaw motorcycle culture that the biker cut truly solidified its place. Even before the explicit split between “family clubs” and outlaw clubs, the practice of wearing cut-off vests, or “cuts,” began. Bikers started removing the sleeves from denim and leather jackets to create vests, providing a base for displaying their club “colors” and patches.

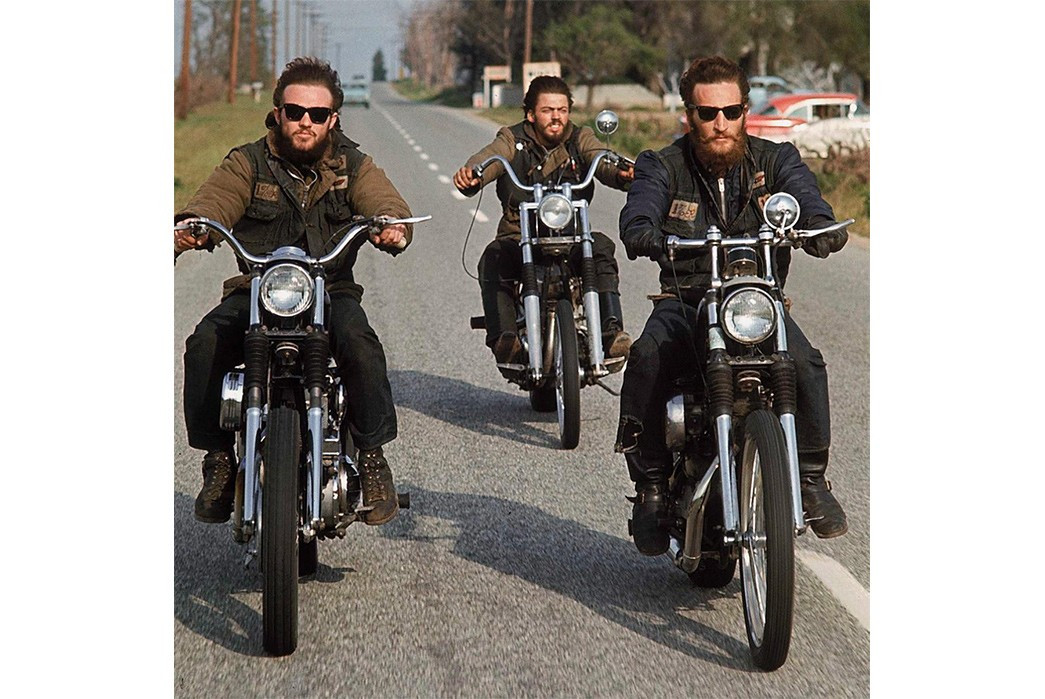

Hell’s Angels mid-60s. Image via NY Daily News.

Hell’s Angels mid-60s. Image via NY Daily News.

Initially, biker cuts were often crafted from denim jackets, prized for their durability and versatility. Denim cuts offered a degree of protection while remaining wearable in warmer weather, especially when layered over other garments like deck jackets, as seen in the image above. Over time, leather became an increasingly popular material for biker cuts due to its superior protection and rugged aesthetic. However, regardless of the material, the “colors” remained the most crucial element of the biker cut.

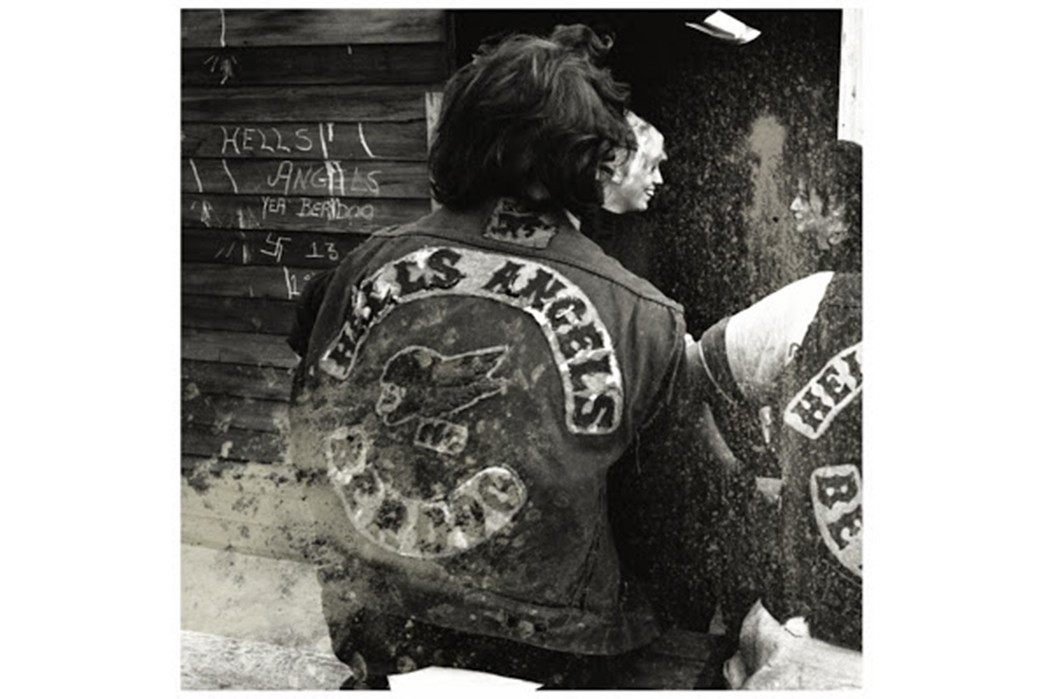

Hell’s Angels Berdoo Chapter, 1965. Image via Life.

Hell’s Angels Berdoo Chapter, 1965. Image via Life.

“Family clubs” or AMA-sanctioned clubs typically displayed their colors as a single large back patch. Outlaw motorcycle groups, however, adopted a three-piece patch system for their colors. This consisted of a central logo representing the club’s emblem, a top rocker patch indicating the club’s name, and a bottom rocker patch denoting their territory or chapter. The front of the cut often featured smaller patches displaying the rider’s nickname and, for senior members, their rank within the club.

Model wearing Iron Heart Japanese Steerhide Modified Type III Vest (front and back view)

Model wearing Iron Heart Japanese Steerhide Modified Type III Vest (front and back view)

The symbolism of biker cuts and colors extends beyond club membership. “Support clubs” or satellite groups associated with larger OMGs are sometimes permitted to wear colors, but crucially, they are never allowed to wear the insignia of the dominant club. Wearing the main club’s logo without authorization is a serious transgression with potentially severe consequences within outlaw biker culture. Similarly, the 1% diamond patch is exclusively reserved for full-fledged members of major Outlaw Motorcycle Groups and is not to be worn by just any club or individual.

While the outlaw biker aesthetic, including the biker cut, may hold a certain allure, it’s important to acknowledge the darker aspects associated with OMGs. Many one-percenter clubs have documented links to criminal activities, and a significant number of these groups historically, and unfortunately in some cases, currently, exhibit white supremacist leanings.

The Biker Cut Today: Fading Outlaw Culture, Enduring Style

Image via Hexis Cyber.

Image via Hexis Cyber.

Despite sensationalized portrayals in media and law enforcement publications, outlaw motorcycle culture is arguably in decline. The major OMGs are facing a demographic shift, with many original members aging out. The traditionally insular nature of these groups and strict membership rules have also hindered the influx of new members. While some OMGs persist, their activities are often less focused on criminal endeavors. Ironically, many current members hold conventional jobs, reflecting a changing demographic and economic reality. The cost of modern motorcycles, like a Harley-Davidson, can easily reach $40,000, requiring financial stability that contradicts the stereotypical image of the outlaw biker.

Despite the evolving nature of outlaw biker culture, caution remains advisable. Wearing a biker cut that closely resembles the colors of a one-percenter group can still be risky, particularly in certain territories. Incidents like the 2015 Waco, Texas shootout between rival biker gangs, resulting in fatalities and injuries, underscore the potential for violence. Navigating biker territories, especially unknowingly, could lead to unwanted confrontations.

However, the cultural impact of the one-percenter clubs and their iconic biker cuts is undeniable. Despite a history marked by violence and controversy, they have profoundly influenced style and popular culture. The biker cut, initially a functional garment for displaying club allegiance, has transcended its origins to become a symbol of rebellion, individuality, and a distinct aesthetic that continues to resonate today.

bikers outlaws vests