While the bicycle might seem like a simple invention with a straightforward history, the truth is far more complex and filled with debate. Pinpointing the exact inventor of the bike is not as simple as it appears, as the evolution of the bicycle was a gradual process involving numerous innovators and iterations over centuries. The earliest forms of human-powered wheeled vehicles bear little resemblance to the modern bicycles we enjoy today, making the question of “who invented the bicycle” a fascinating journey through engineering ingenuity and societal needs.

Long before the sleek road bikes and mountain bikes of today, the concept of a human-powered vehicle on wheels began to emerge. One of the earliest documented examples dates back to 1418, when Giovanni Fontana, an Italian engineer, designed a four-wheeled device propelled by a rope and gear system. According to the International Bicycle Fund (IBF), Fontana’s invention, while not a bicycle in the modern sense, represents a significant early step in the development of human-powered transportation.

However, it wasn’t until the early 19th century that a more direct ancestor of the bicycle appeared. In 1813, Karl von Drais, a German aristocrat and inventor, started working on his “Laufmaschine,” or running machine. By 1817, Drais introduced a two-wheeled version of his machine. This vehicle became known by various names across Europe, including Draisienne, dandy horse, and hobby horse, marking a pivotal moment in bicycle history.

Baron Karl von Drais demonstrating his Draisienne, an early precursor to the bicycle, in France, 1817

Baron Karl von Drais demonstrating his Draisienne, an early precursor to the bicycle, in France, 1817

The Draisienne: A Response to Necessity

Karl von Drais’s invention of the Draisienne was not born in a vacuum. It was a direct response to a severe environmental and economic crisis. The eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia in 1815 caused a global ash cloud that dramatically lowered temperatures worldwide. This led to widespread crop failures and the death of many animals, including horses, as detailed by Smithsonian Magazine. Horses, the primary mode of transportation at the time, became scarce and expensive.

The Draisienne offered a timely alternative. These early bikes, however, were quite different from contemporary bicycles. Weighing around 50 pounds, the Draisienne featured two wooden wheels on a wooden frame. Riders sat on a leather saddle and steered with wooden handlebars. Crucially, it lacked pedals; propulsion was achieved by the rider pushing their feet against the ground.

Drais presented his invention in France and England, where it gained considerable popularity. Denis Johnson, a British coach maker, capitalized on this trend and marketed his own version, called “pedestrian curricles,” to wealthy Londoners. For a few years, hobby horses were fashionable. However, their popularity waned in the 1820s as they were banned from sidewalks due to safety concerns for pedestrians, according to the National Museum of American History (NMAH). These early bicycles largely disappeared from public view for several decades.

The Velocipede and the Pedal Revolution

The bicycle experienced a resurgence in the 1860s with the arrival of the velocipede, also known as the “bone shaker.” This machine, typically made of wood with steel wheels, incorporated pedals and a fixed gear system. Riding a bone shaker was, as the name suggests, a rather jarring experience.

The origins of the pedal-equipped velocipede are somewhat unclear. Karl Kech, a German, claimed to have added pedals to a hobby horse in 1862. However, the first patent for such a device was awarded to Pierre Lallement, a French carriage maker, who received a U.S. patent in 1866 for his two-wheeled vehicle with crank pedals, according to the NMAH.

Prior to patenting his invention, Lallement publicly displayed his velocipede in 1864. This exhibition may have inspired Aimé and René Olivier, sons of a wealthy Parisian industrialist, and their classmate Georges de la Bouglise to develop their own velocipede. They partnered with Pierre Michaux, a blacksmith and carriage maker, to produce the necessary parts.

Michaux and the Olivier brothers began selling their pedal velocipedes in 1867, and they became a sensation. Although disagreements led to the dissolution of their initial company, the Olivier-owned Compagnie Parisienne continued to thrive.

By 1870, riders were seeking improvements over the uncomfortable bone-shaker design. Advances in metallurgy allowed for the use of metal in bicycle frames, making them lighter and stronger than wooden frames, as noted by the IBF. This paved the way for new bicycle designs and innovations.

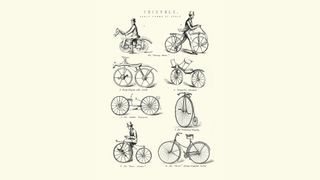

A 19th-century illustration showing the evolution of early bicycles, including the Dandy Horse, Velocipede, and Bone Shaker

A 19th-century illustration showing the evolution of early bicycles, including the Dandy Horse, Velocipede, and Bone Shaker

From Penny-Farthings to Safety Bikes: Towards Modern Bicycles

One notable design that emerged was the high wheeler, or penny-farthing. Its name came from the British penny and farthing coins, reflecting the significant size difference between the front and rear wheels. Penny-farthings offered a smoother ride than bone shakers due to their solid rubber tires and long spokes. Manufacturers increased the size of the front wheel, as a larger wheel covered more distance per pedal rotation. Enthusiasts could ride penny-farthings with front wheels as tall as their legs allowed.

However, the penny-farthing’s design was inherently dangerous. Sudden stops could send the rider pitching forward over the high front wheel, leading to the expression “taking a header.” Despite this risk, penny-farthings were popular among thrill-seekers and racers in newly formed bicycle clubs across Europe.

The impracticality of the penny-farthing for most riders led to the development of the “safety bicycle.” John Kemp Starley, an English inventor, is credited with this crucial innovation in the 1870s.

Starley began successfully marketing his bicycles in 1871, introducing the “Ariel” bicycle in Britain. This marked the start of Britain’s dominance in bicycle innovation for many decades.

Starley’s 1874 invention of the tangent-spoke wheel was a significant advancement. This tension-absorbing front wheel greatly improved ride comfort and reduced weight compared to earlier wheels.

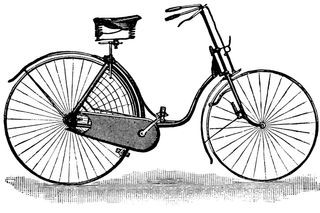

In 1885, Starley unveiled the “Rover.” Featuring nearly equal-sized wheels, center pivot steering, and a chain-drive differential gear system, the Rover was remarkably stable and represented the first truly practical bicycle design.

The impact of Starley’s safety bicycle was immense. The number of bicycles in use surged from approximately 200,000 in 1889 to 1 million by 1899, according to the NMAH.

Initially, bicycles were a luxury item. Mass production made them affordable for working-class individuals, enabling them to commute to work and expanding leisure opportunities. The rise in female cyclists also spurred significant changes in women’s fashion, with bloomers replacing restrictive bustles and corsets for greater mobility and modesty.

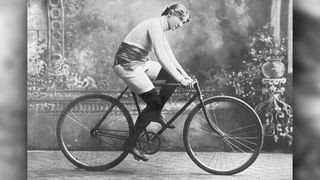

A woman riding a safety bicycle, showcasing the design and its impact on female mobility in the late 19th century

A woman riding a safety bicycle, showcasing the design and its impact on female mobility in the late 19th century

Bicycles also played a role in improving road infrastructure. Cyclists advocated for better road surfaces, which benefited not only bicycles but also horse-drawn vehicles and, later, automobiles. Railroad companies joined this movement to improve connections to rail stations.

The bicycle directly influenced the development of the automobile, according to the NMAH. Bicycle components like ball bearings, differential units, steel tubing, and pneumatic tires were incorporated into early automobiles. Many pioneer car manufacturers, including Charles Duryea, Alexander Winton, and Albert A. Pope, were initially bicycle manufacturers. Even aviation pioneers Wilbur and Orville Wright started as bicycle makers before turning to flight.

However, the popularity of automobiles led to a decline in bicycle use in the early 20th century. Electric railways also took over bicycle paths. Bicycle manufacturing decreased, and for over 50 years, bicycles were primarily seen as children’s toys.

The Bicycle Renaissance and Modern Innovations

Adult interest in cycling revived in the late 1960s as people sought non-polluting and non-congesting transportation and recreation options. In 1970, nearly 5 million bicycles were manufactured in the United States, and an estimated 75 million riders used 50 million bicycles, making cycling a leading outdoor recreational activity in the nation, according to the NMAH.

Tillie Anderson, a champion cyclist, demonstrating the athleticism and popularity of cycling in the late 19th century

Tillie Anderson, a champion cyclist, demonstrating the athleticism and popularity of cycling in the late 19th century

Today, over 100 million bicycles are produced annually, according to Bicycle History, and approximately 1 billion bicycles are in use worldwide.

Modern bicycles are incredibly diverse. Frames are constructed from materials like steel, aluminum, titanium, carbon fiber, and even bamboo, depending on the intended use. Wheels vary in size and thickness for different terrains, from mountain trails to city streets. Riders can choose from various brakes, gear systems, seat designs, handlebar styles, and suspension options.

Modern bicycle designs have evolved dramatically. Folding bikes offer portability, seatless bikes provide a different riding experience, bikes with child carriers facilitate family cycling, and electric bikes add motorized assistance.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Innovation

So, who is the inventor of the bike? The answer is not a single person, but rather a series of inventors and innovators who progressively developed the bicycle over centuries. From Fontana’s early concept to Drais’s Draisienne, Lallement’s pedals, Starley’s safety bicycle, and countless modern advancements, the bicycle’s history is a testament to continuous improvement and adaptation. The bicycle’s journey reflects a fascinating interplay of necessity, ingenuity, and evolving technology, making it one of the most impactful and enduring inventions in history.

Further Resources

Explore the evolution of the bicycle through images at the Bicycle Museum of America’s website. Learn about bike infrastructure’s role in cyclist safety from Reliance Foundry. Discover the benefits and risks of cycling in an international study published in Transportation Research.

Additional reporting by Rachel Ross, Live Science contributor, and Tim Sharp, Reference editor. This article was updated on Feb. 25, 2022 by Live Science senior writer Mindy Weisberger.

References

“Bicycle History (& Human Powered Vehicle History).” Bicycle History Timeline, http://www.ibike.org/library/history-timeline.htm.

Magazine, Smithsonian. “Blast from the Past.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 July 2002, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/blast-from-the-past-65102374/.

“America on the Move.” National Museum of American History, 3 July 2019, http://amhistory.si.edu/onthemove/themes/story_69_2.html.

“Bicycle History – Story of Two-Wheelers for Transportation.” Bicycle History – Evolution of Cycling, http://www.bicyclehistory.net/.

“Bicycle History.” THE BICYCLE MUSEUM OF AMERICA, http://www.bicyclemuseum.com/bicycle-history/.

“Essential Guide to Bike Infrastructure.” Reliance Foundry Co. Ltd, 17 Jan. 2022, https://www.reliance-foundry.com/blog/bikeways-bike-infrastructure.

Useche, Sergio A., et al. “Healthy but Risky: A Descriptive Study on Cyclists’ Encouraging and Discouraging Factors for Using Bicycles, Habits and Safety Outcomes.” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, Pergamon, 4 Mar. 2019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1369847818306934.